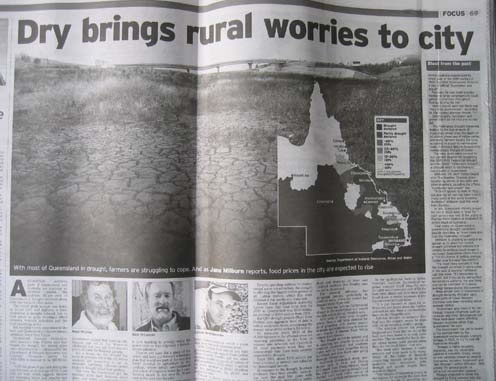

| Although northern

parts of Queensland and Australia are enjoying an excellent season,

the bottom 60 percent of Queensland is drought declared along

with vast tracts of southern states.

The winter grain harvest was down by 60 percent,

and AgForce is foreshadowing a drought-induced rise in food prices

as grain shortages impact on intensive livestock industries and

the food processing sector.

But hardship breeds innovation in the bush

and Queensland producers remain optimistic about their future.

Queensland Farmers Federation chief executive

John Cherry says that despite the drought, the annual gross value

of production – calculated by the Department of Primary Industries

and Fisheries’ Prospects survey – for 2005-2006 is forecast to

be $10.93 billion.

“GVP has grown 9 percent

during past five years at an average of 1-2 percent per year,

which suggests farmers are managing better and smarter and just

getting on with the job despite the growing water shortage.”

The 1994/95 drought was the wake-up call for

fifth generation farmer Linton Brimblecombe, who says it was the

driver for a new way of thinking about securing the water that

underpins farming in the Lockyer Valley.

That drought led Linton to invest $2 million

in water infrastructure and dams to secure his water supply, as

much as that is possible. The State Government missed that wake-up

call, because rain fell in the Wivenhoe catchment that year and

there was still plenty of water for Brisbane.

But a decade on, this drought has made its

presence felt in the city where residents on are scrambling to

set up rainwater harvesting schemes (water tanks) to drought-proof

their gardens.

This time the government got the message,

some hard decisions about dams and water infrastructure have been

made, there’s a plan to drought-proof the cities in the south

east with a grid to move water around as required.

“Queensland must not get complacent, we must

not miss another opportunity for infrastructure building,” says

Linton, a beetroot grower who supplies Golden Circle.

It was the Lockyer farmers who conceived the

idea of recycling Brisbane’s wastewater. The western corridor

pipeline the State Government is now building to provide water

for power stations was originally a farmer-driven initiative.

They’re still keen for a piece of the action

and have put forward a business plan that would see part of the

recycled water diverted to agriculture in the Lockyer, where urban

encroachment and a lack of irrigation water have seen farming

shrink in the area by 30 percent in the past two decades.

“We’re not whingeing farmers looking for handouts.

Farmers are willing to put up $50 million to make this happen

and we’re looking to the National Water Initiative to put up the

other $50 million.”

Although farmers are used to dealing with

challenges from the elements, with each drought it gets a little

harder and requires constant innovation.

It was the desire to sure up his water supply

that drove Gatton orchardist Ross Stumke to source recycled water

from Gatton township, which is piped 7km from the local treatment

plant.

With funding from federal and state government,

and support from Gatton Shire Council, Ross and two other farmers

secured an annual allocation of 100 megalitres in 2002 which is

applied by micro sprinkler or trickle irrigation to his persimmon,

fig, peach and nectarine trees.

“Water is always going to be our greatest

limiting factor and we have to carefully monitor its use because

we have just enough for our current crops and no room to expand.”

On the Darling Downs, Jeff and Marilyn Bidstrup

won’t be planting any cotton this season after being industry

leaders for years. The Bidstrups have chosen to use what little

water they have to grow sorghum, which will tolerate running out

of water better than cotton will, and have faith that it will

rain before that water runs out.

Despite spending millions on controversial

water infrastructure, the drought is impacting on the biggest

cotton grower of all, Cubbie Station, which this week declared

it has hardly any water left.

Recent Rural Adjustment Authority

figures show that total farm debt for 2005 in Queensland was $8.67

billion, an increase of $966 million from 2003.

But QFF drought project officer Peter

Perkins says that aggregate level of debt is within acceptable

levels, considering the annual value of the sector is $11 billion.

He estimates about 5000 of the 18,000

farmers in the affected areas are receiving assistance, in the

form of interest rate subsidies and Centrelink EC relief payments

when they can demonstrate they have been severely impacted by

drought.

Since 2001, about $300 million has

been provided as interest rate subsidies to Queensland farmers.

In response to the drought, livestock

producers have been steadily destocking over the past few years

with Australia’s biggest cattle selling centre at Roma having

record throughput of 408,000 cattle in 2004, and 370,000 in 2005,

according to Roma Saleyards market reporter John Gilfoyle.

“There have been a lot more store

cattle coming on to the market during the past two years, but

there is strong demand, particularly from northern producers,

who have had good rains from the cyclones earlier in the year,”

says Gilfoyle.

So is it the end of the boom time for cattle? North Queensland

cattle producer and chairman of Meat and Livestock Australia Don

Heatley says no, not in Queensland.

The seasonal influence has dampened

demand, particularly in southern states, where the market has

dropped about 25 percent.

“But there has been no fundamental

change in the marketplace and export markets remain strong,” Heatley

says.

After years of rising cattle property

prices, there is still keen demand for good properties, with money

readily available and relatively cheap to borrow says founder

of Herron Todd White valuers Kerry Herron.

“But drought cannot be ignored and

is impacting very severely on much of southern Queensland, and

southern states, with far fewer properties are being advertised,

and even fewer sales going through,” says Herron.

South west Queensland sheep producers

such as Dick and Donna O’Connell, from Thargomindah, faced the

reality of the ongoing drought and decided their most viable course

of action was to destock and preserve their financial position.

Over the past five years, they progressively

sold-off sheep and cattle while they were still in good condition

and used the proceeds from those sales to retire farm debt and

invested what was left off the property.

“Each year the drought continues

makes us glad we decided to sell the stock,” says Dick, who remains

optimistic that despite this run of rotten years, things will

come good.

In the agribusiness banking sector,

Suncorp’s southern Queensland regional manager Geoff Magoffin

says droughts are an everyday part of life for their rural clients

and most have plans to sell down, or contain expenses, as any

business does in tough times.

“It is just business as usual for

us. Producers just batten down the hatches and wait for rain,

there is not much else they can do.”

AgForce drought coordinator Rod Saal

says the country people he deals with are an incredibly resilient

group.

“The selection process has already

happened and those that are still in the bush have been tested

by its cold, harsh realities. They’re wonderful, hardy people

whose human spirit armour-plates them for the tough times,” says

Rod.

“But rural small business is under

pressure and there needs to be recognition of the value of financial

counselling because people do have problems with depression, debt,

drought and suicide despite their overall resilience.”

“The benefits of supporting people

in the regions far outweigh the costs that government invests

in providing another tool (farm financial counselling) for people

in the bush to access so they continue to be viable.”

|